By Laurein Drumm

Bixby High School

After a lack of calls back from employers and rejected applications, a formerly incarcerated woman decided to do what many with felony convictions eventually do to find employment: lie on her job application.

This resulted in her getting a job at a popular fast-food chain where she worked for nearly a year. She put in long hours to support her and her family, and even was promoted to management.

Then the company began implementing background checks and her status as a felon was revealed.

Soon there were accusations that money had gone missing and the woman was skipping her shifts, which led to her termination.

“People think if they hire them or go into the business they’re going to be working with horrible people. “It’s just not the truth” said Juanita Ortiz, executive director for faculty and staff advancement and institutional research at Rose State College, in recounting the anonymous woman’s story. Ortiz holds a doctorate in sociology and wrote her dissertation on recidivism of female offenders in Oklahoma.

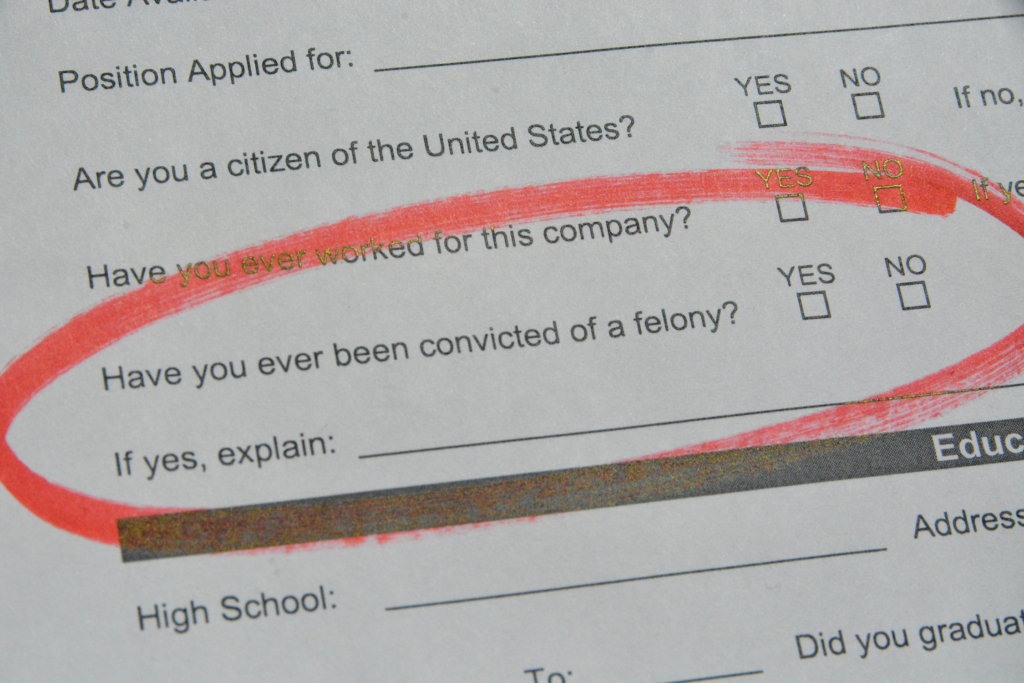

Many states have adopted “Ban-the-Box” initiatives, advocating for removing the checkbox that requires applicants to disclose whether they have a criminal record. However, Oklahoma has not.

Ortiz said that in the world of crime, women are often perceived to have more lenient sentencing and repercussions, whereas in Oklahoma it’s the opposite. A man and woman who both abuse substances or commit crimes are not likely to have the same societal and legal response to their actions.

“I think it’s perceived, especially in Oklahoma, that a woman that’s a mother and a woman that does drugs is seen as the worst kind of person,” Ortiz said. “Or a woman who commits a crime is just horrible, whereas men do these things and are seen as redeemable (by society).”

Due to Oklahoma having the largest incarcerated female population in the United States, one consisting largely of single mothers, low-income women re-entering society are faced with disproportionate job discrimination.

“It’s such a conservative, religious state that women’s violation of gender roles, like being the proper mother (and) being the proper woman, is so highly punished,” Ortiz said.

The gender roles following women with felonies, especially mothers, compound the job discrimination.

“It’s a total demonization of women,” Ortiz said.

When mothers who are most likely to commit crimes are low-income and lack a support system, they re-enter society with the burden of not only supporting their children and themselves, but also building a stable life from scratch.

Re-entering society comes with excessive fines, deadlines and constant parole surveillance. The Prison Policy Initiative has concluded that “unemployment is highest for people released in the last two years, when they are most vulnerable to re-incarceration.” When the lack of employment leaves these women without any options, sometimes they return to crime.

The final decision to “Ban-the-Box” may fall on the employer, but the way individuals respond to a felony status is just as important. Ortiz said that unlearning stereotypes and promoting de-stigmatization among women with felonies will ultimately create an environment that encourages their return and success.

“Have discussions with people you know,” Ortiz said. “They’re likely to listen to you. Join local groups in public to show numbers. Develop stories and expose these issues in class assignments or wherever you have someone to listen. Talk about it.”