By Eboni Montgomery, Crowley (Texas) High School

On average, teachers work 53.3 hours a week teaching and doing school-related work, according to a job recruitment website Zippia. That doesn’t even include the work they might have to do at home like grading papers and creating lesson plans because they don’t have time at school. Hillary Cowen experienced this first hand to the extent that she quit the career she loved.

Cowen taught middle school Spanish at a public charter school for 16 years. She quit teaching last January and is now working as a banker. She has a bachelor’s degree in Spanish arts. She wanted to go back to school to get her master’s degree but realized that it would not significantly increase her salary.

“(The current education system was) setting me up to fail every single day,” Cowen said. “Listen, if I was paid a billion dollars to fail at my job everyday, that would be one thing. But most teachers have second and third jobs on top of teaching. I did. I was working the front desk at a massage spa.”

Cowen said that teachers get paid on this scale based on how long they have been a teacher. She was on the higher end of the teacher salary because of her experience in teaching. In the eight years she taught her salary increased only a couple hundred dollars.

When she left, her salary was around $48,000.

Oklahoma is one of the lowest paying states for teachers, according to nonprofit project PolitiFact. Cowen said that Oklahoma is known for its teacher preparation program. Oklahoma State University is ranked No. 1 for the best college for education in the state. A lot of teachers don’t stick around in Oklahoma because they can find better pay in other states.

“Everybody knows that you make more money teaching in Texas or Arkansas than Oklahoma,” Cowen said.

Because of the teacher shortage, Oklahoma provided 3,690 emergency certified teacher certificates last November, according to KOSU. Cowen said that students are not getting a proper education to learn because they have inexperienced teachers.

“Literally, they give anyone with a pulse an emergency teaching certificate right now,” Cowen said.

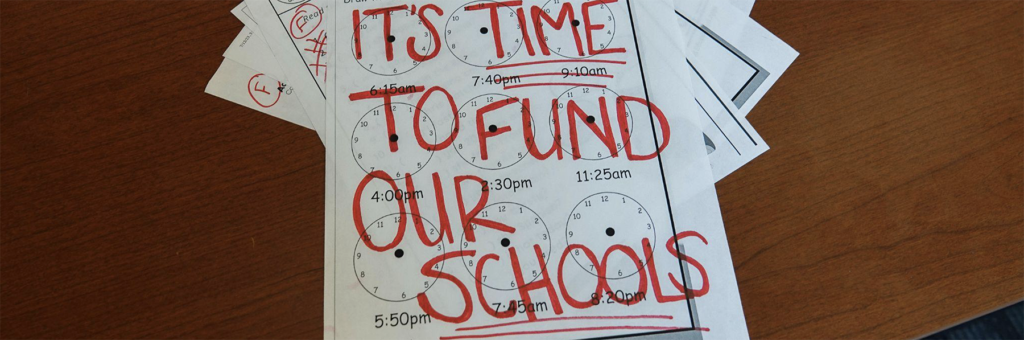

In 2018, there was a huge teacher walkout to protest low pay and overload class sizes. It lasted for 10 days. Cowen participated and said it was ineffective. She said the legislators told them to go back to work, not wanting to meet with the teachers and disparaging them.

“We were protesting to get improvement for the students and legislators made it so that we were unhappy about pay,” Cowen said.

Another teacher who participated in the walkout was Amy Emmons. She was also there fighting for her students and for increased funding. She said when districts don’t supply certain things or enough resources, the teachers have to go out and get it themselves.

“There is hardly any job that you have to bring your own supplies to besides teaching,” Emmons said.

Emmons has a bachelor’s degree in communication sciences and disorders and a master’s in special education. She has been teaching for 25 years and currently teaches elementary special education.

She got to talk to a senator about it and felt he was condescending. She feels there is a lingering tension between teachers and lawmakers as some politicians continue to bring up the walkout years later.

“I don’t feel like lawmakers respect teachers,” Emmons said.

Coming from a parent perspective, Cowen said she is glad her son has one more year of school left because there is not a lot of quality education in the classroom. Some of her friends have younger kids who haven’t started school yet and they are saving for their children to go to private school.

“I’m glad my kids are finishing up,” Cowen said. “I’m glad I’m not at the beginning of this…I feel really, really sad about where public (education) is right now.”

Cowen explained that she wasn’t allowed enough time in her work schedule to do everything her boss asked. She said at her last school, she taught three Spanish classes. She wasn’t given any extra planning time, so she had to create three lesson plans in one 45-minute class period.

“You (are) not given enough time to do anything you need to do,” Cowen said. “(We) were asked to do a ridiculous amount of paperwork but we are not given any additional planning time.”

Cowen talked about how being a teacher can affect a person’s mental health. She said they can get insomnia, anxiety attacks and panic attacks. Some teachers also experience something called Sunday scaries, which is a feeling of nervousness that some people get before going back to work or school on Monday.

She also said that some teachers have trouble disciplining their students. She remembered hearing stories about kids making inappropriate drawings of their teachers and even kids who threatened their teachers.

“My mental health is changing at every turn,” Cowen said.

Emmons said that another challenge of being a teacher is dealing with the parents and the students. She said that some parents will find a way to blame the teacher when their child gets in trouble. She also said that parents expect so much from teachers outside of work.

“You’re not just doing your job on your contract time,” Emmons said. “You are often doing (your job) before you get to work (and at) dinner time.”