By Sofiіa Korol

On Feb. 24, at 4 a.m., Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. For five months now, missile attacks on military and civilian infrastructure have been taking place every day across the country. Martial law has been declared in Ukraine. Due to constant shelling, civilians are hiding in basements, there is no food or water in hot spots, and the occupiers are tearing down green corridors and preventing the delivery of humanitarian aid. Every day there are new reports of horrific actions by the Russian military (such as the rape of teenagers or the killing of innocent children).

In order to escape the Russian occupation and save their lives, some Ukrainians had to leave their homes and go to neighboring countries.

Polina and Timofey agreed to become the heroes of the article and share their experience of moving to a foreign country and how they managed to start a temporary life there.

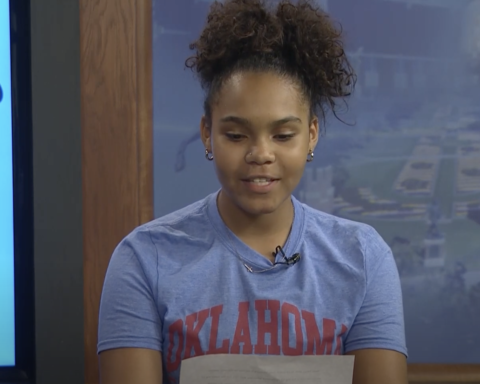

Ukrainian journalist Sofiіa Korol spoke with them. Sofіia is a student of the Faculty of Journalism of Chernivtsi National University, a Young European Ambassador and a participant in various Erasmus+ youth exchanges. She is primarily interested in ecology, gender equality, and media literacy, but Feb. 24 radically changed her life as well. Now she is in England, doing volunteer work and helping people who are forced to leave their homes.

“Wake up, the war has begun:” Polina’s story

Polina is 18 years old. She was born in Kryvyi Rih, lived and studied in Kyiv at Kyiv National University. She worked with children for more than four years and organized children’s holidays. She also worked as a presenter, animator, decorator, manager, and theater teacher for children as well as a babysitter.

“The war caught me in Kyiv,” Polina said. “In the morning, a neighbor in the dormitory ran into the room with the words ‘Wake up, the war has begun!’ For the first 20 minutes I did not understand what was happening. There was an explosion, a siren, fog—they ran to the basement. At 10 a.m. I ran to withdraw money, cried and prayed.”

The young woman remembers that moving was the most difficult. The next day after the start of the war, she went to the station, where there were already thousands of people. The bus for which she bought a ticket did not arrive. So, with tears in her eyes, she begged every driver to take her. After three hours of trying, I ran to the departing bus, and the driver said: “There are no seats, you won’t stand.” And Polina said, “I will!!” And he took her. Subsequently, the she rode, standing, for 10 hours to the border.

Then they were distributed to buses with other passengers. She waited 18 hours at the border in line. She had small children in her arms. Polina does not know whose. They were just there and slept, and she did not move so that they slept and did not see that horror.

“We were already standing at the entrance to the customs house when we heard shots. Children started screaming and crying, adults ran in panic,” Polina continued. “I grabbed the passport in my hand, took a deep breath, as if for the last time, and waited for them to tell me where to run. Carried away, the military shot down the drone and it was all over. In total, it took 42 hours to get to Poznań. Friends met us there.”

In Poland, she rested for four days and went to Tallinn to visit her father. Later, her mother and sister also arrived. Polina started looking for a job and later turned to the hotel where they temporarily lived. This company has a tour business, and so she was offered to work as a flight attendant on a ship, because she knew English.

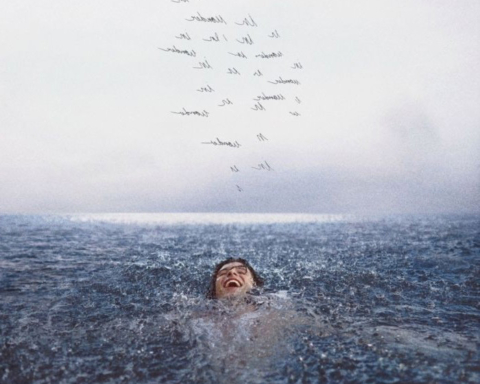

And Polina has been working at sea for more than three months. By chance, she met a girl from Kyiv in a hotel who had graduated from the same faculty where Polina is studying. So, she had one friend. She said nature and walking and the support of a friend have helped a lot.

“I’ll walked alone along the sea, or through the forest and just think. I had to work through a lot of psychological problems myself. Nature probably helped. And music.

“Working is difficult. All the time you are rocking in the sea, there are certain language barriers (when people speak Estonian at dinner at work, and you don’t understand and they don’t always translate for you). Finishing the semester at the university online while combining it with work was another quest. And I lost my scholarship. It’s also sad without all my friends. And I really want to return to my past life, but it’s impossible,” Polina explained.

Polina’s boyfriend waited for her in Poznań (he worked there before the war). And the next morning after the meeting, the girl received a message from him.

“I crossed the border, I’m sorry, I couldn’t do otherwise.”

She cried, but tears would not help. He went to defend Kyiv. When the north was released in March, Polina received a new message.

“I’m going to Mariupol, my boys are going, I can’t do it any other way.”

On March 30, he was already there. He disappeared for a week. On April 6, he wrote that he was alive and the connection was lost.

Today is 101 days since Polina has heard his voice, and she does not know where he is or how he is. The first 50 days were the hardest, she said. Because at times it consumed her and realizing that Mariupol was under full occupation, she feared more than anything that he was no longer alive. But she promised herself to believe and pray until the end.

On May 25, she called the Iryna Vereshchuk Foundation from abroad and was told he was alive in the base as an evacuee from Azovstal.

More tears, but happy ones. And to this day she thanks God for saving his life and health. A friend of his recently called, who returned from captivity, said that he is “healthy, has lost weight, loves me and is worried if I am waiting.”

“And I’m waiting. And I will wait. And I really believe that my sunshine with blue eyes will soon be near. So, for plans for the future are family. Marry a loved one and have children. There is nothing more valuable,” Polina concluded.

“I was traveling with a family I didn’t know:” the story of Timofey

Timofey is 17 years old and graduated from school this year. He lives in the village of Belogorodka, Kyiv region.

“From February 24, explosions and the whistling of airplanes were heard here, sometimes convoys of tanks and armored personnel carriers passed by, the forest was mined. In general, Belogorodka was the border of peace: 15 minutes on the Kyiv-Zhytomyr highway – and the road becomes broken, and shops and gas stations are abandoned, with broken windows,” Timofey described.

The boy will remember that at the beginning of the war, his parents joined the territorial defense, and he and his two younger brothers and sisters, as well as the dogs, were sent to Uman to his grandparents. He spent three months of the war there and said that every day there were two or three air raid sirens. Sometimes enemy planes flew by.

After some time, Timofey’s mother called him. She said that she talked with her acquaintance from Germany about the university and suggested that the boy go there. Timofey wanted to enter the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy for three years, and although he agreed to go to Germany almost immediately, he still hesitated whether to deviate from the intended path.

“I was driving with a family I didn’t know, in a car. These people were friendly and kind, so I am grateful to them. My foreign passport had expired and, although I knew I was being let through, I was still a little afraid when we were at the Slovakian border in the middle of the night. We spent the night in the car, then Austria and, finally, Germany,” Timofii said, remembering his move.

Now he lives with the aforementioned acquaintance together with another Ukrainian family. The biggest difficulties are language and getting an education, and he said his German language skills are his worst, and to tell the truth, he had no plans to use it. Now that he is in Germany, he makes up for it with courses from the German government. With regard to education, one year should be spent to reach B1-B2 level knowledge of the language, and another year for preparatory courses, because here you need to have 12 years of education instead of 11.